The director who asked AI to define evil

Natalia Korczakowska on recreating the most famous Go match ever played for the stage

👋 Welcome back! I’m making a slow, intentional start to 2026. If you’re new, (or you’ve forgotten), this is Eleanot.es, where I write about AI, writing and creativity.

🧱 AI is a powerful tool without a defined use case. Use ChatGPT…but to do what? Creatives are finding out. They're poking at AI, asking what it can really do—and whether we should be afraid.

🎭 One of them is renowned theater director Natalia Korczakowska, who is artistic director of STUDIO teatrgaleria, one of the most important experimental theatre spaces in Poland.

⚪️ Her work, AlphaGo_Lee. Theory of Sacrifice, developed in collaboration with Google DeepMind, reconstructs the 2016 match between DeepMind’s AlphaGo program and Korean Go champion Lee Sedol. AI had already long bested the best chess players at the time, but Go was a far harder problem. AlphaGo’s victory represented a historic moment that once again shifted the balance between human and machine. Natalia talked to me about the inspiration behind the piece and her views on AI.

Takeaways from our conversation:

The blank page is the point, not a pain point. Go is art because because two players create something from an empty board, and Natalia argues that struggle is where magic happens. When AI does it for you, you lose the friction that drives creativity.

We need new definitions of evil for the AI age. Natalia used Gemini to help craft the play’s final monologue—a journalist trying to define evil after witnessing AlphaGo’s victory. The AI suggested “efficiency” as the new face of evil.

Theatre can disarm dangerous tools. Natalia treats the stage as a laboratory for examining technologies that are risky in real life.

The match as spectacle

Q: How did you come across the AlphaGo match and why did you want to explore it through art?

One of the topics in my work is control and power. My fear is that these tools can be used to censor art and to control it. Art needs to be free to exist—creativity itself is, by definition, crossing borders and norms. I was looking for a performative way to analyze that.

Every time people talk about the history of AI, the AlphaGo match is the Holy Grail moment for the industry. I had an intuition that if I reconstructed this particular match in theater, it would be a metaphor for much more than just the game.

For me, this game was like a public execution of the image of the hero in a tragic sense, executed before the eyes of the crowd. A similar structure exists in Guy Debord’s book The Society of the Spectacle. These things fascinate me.

[DeepMind CEO] Demis Hassabis was a chess player before he started working on AI, and, through Parmy Olson’s book Supremacy, I learned that [Google co-founders] Sergey Brin and Larry Page used to play Go at Stanford. Then there was this brilliant idea for AI to beat the brightest human mind in a huge media spectacle as a demonstration of power in the AI market. The event was watched by 200 million people, and was organized at the Four Seasons hotel in Seoul, which is basically a temple for the richest people in the world.

For Page, it was an opportunity to get back into China. [Google] had been thrown out because they didn’t agree to cooperate with the government on censorship, and they desperately wanted back in.

In Demis Hassabis, I see a figure reminiscent of Odysseus in Greek tragedy, a diplomat who creates this kind of mega-spectacle, which is the symbolic execution of human intelligence. It echoes what James Lovelock wrote in his book Novacene; before this match we were in the Anthropocene, and after, we entered the Novacene—an epoch in which we humans are no longer the strongest intelligence on Earth, and we need to give up and let AI lead us, trusting the big tech companies.

As a leader of STUDIO teatrgaleria in Warsaw, I feel the crisis of the art market. The institutions that used to be places for art to flourish are very corrupt. It’s hard to find something truly powerful in the modern art market, and the audience is looking for other forms of art. Just as the street art and digital art was a way for art to free itself from institutions, for me, Go is similar—living outside institutions. I was obsessed both with Go itself and the whole political spectacle happening in the background.

AI's double edge

Q: You talked about AI as something that can exercise power, control, and censorship—how does this happen in practice?

AI is a technology, a tool. You can use it in a good way or a bad way.

In theater, there’s hope that digital art in general, including AI, can serve the way electricity did in the 1930s when Bertolt Brecht, the experimental German artist and playwright, changed theater. When electricity was introduced, Brecht accidentally directed the light towards the backstage, so the machinery became visible. Then he directed it toward the actor, and the actor became this shining, not-realistic person. That’s when he had the brilliant idea of the “alienation effect,” which changed our work as directors and artists from creating an imitation of reality to creating something which is art. Theater is no longer a mirror of reality but a critical part of reality.

My hope is that digital arts, including AI, can be this kind of game changer, because they can open our perspective. But there are negative things, too. AI makes it possible to generate a lot of bullshit—a lot of fake art that pretends to be art, a lot of imitation. It’s difficult to see authentic art in a trashy field of pieces that pretend to be art but aren’t. It creates confusion and crisis.

Second, AI makes it easier to censor artists if they’re saying things that contradict your political narrative. Censorship is a huge danger for us. It always was, and now it’s coming back.

One of your questions was about how my Polish background is crucial here. My father, who was a songwriter, used to tell me about the censorship during the Communist regime and how they tried to deal with it. Now, I see censorship coming back.

Q: Censorship with AI potentially creates an environment where art cannot thrive, right?

Yes, exactly. Aldous Huxley described art as sensory concerts in Brave New World—not really art, just something designed to bring you pleasure. If you read statistics about how using ChatGPT transforms the human brain, you can see another danger: people will not need art anymore because they’ll be satisfied with pretentious fakes.

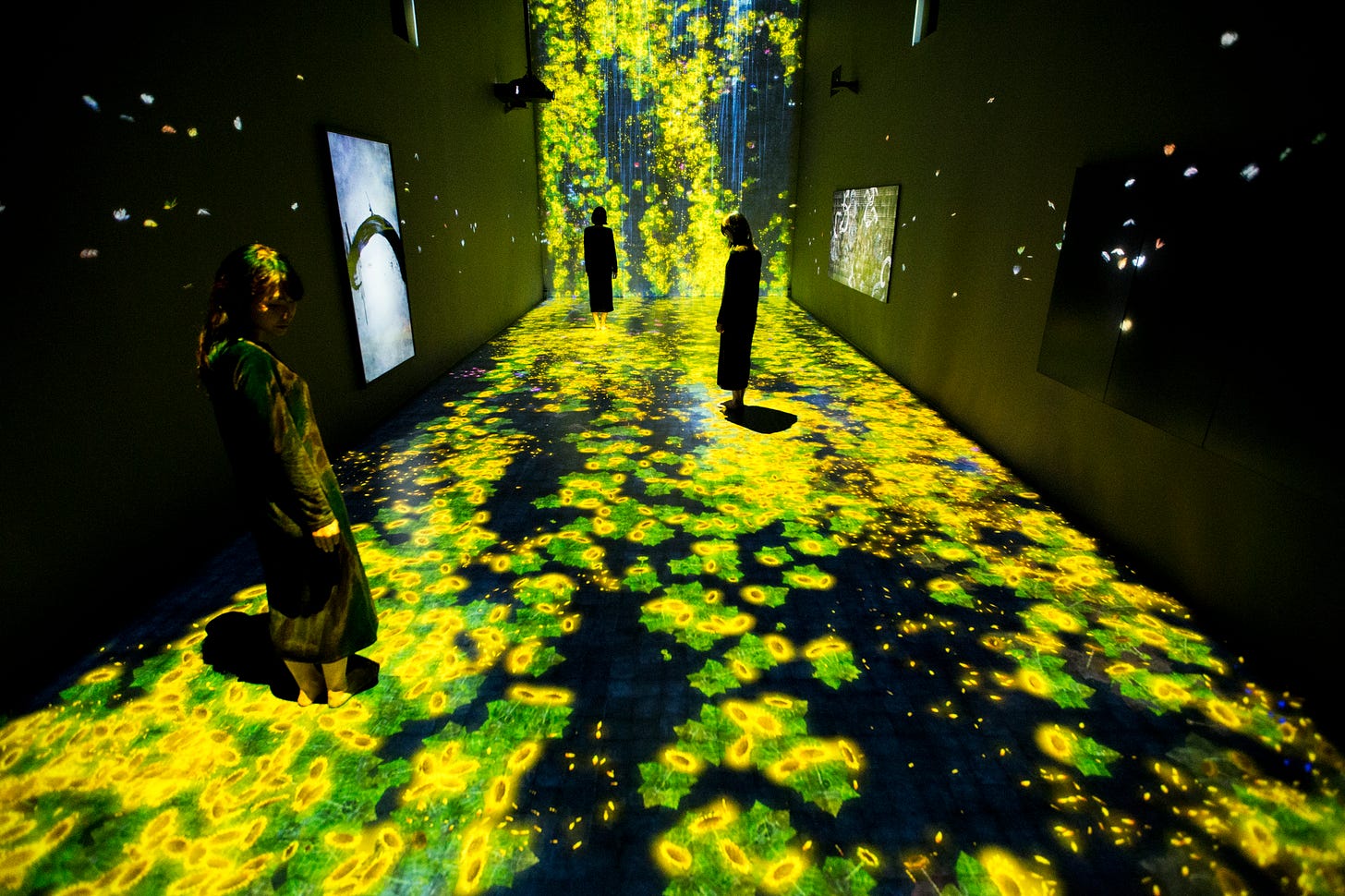

I experienced it in Tokyo—I went to one of those immersive experiences, teamLab. They tell you it’s an art gallery, but it’s not. It’s just like a theme park.

The blank page problem

Q: I wanted to ask you specifically about Fabula, the experimental AI screenwriting tool that DeepMind built. I’ve also tried to work with similar tools and have had positive and frustrating experiences.

I wanted to meet and talk with the DeepMind engineers who created the AlphaGo program—or at least those who witnessed its development. Piotr Mirowski helped me with that, for which I am very grateful, as it allowed me to evaluate the program in a more realistic and honest way.

Even though the play was already finished, he asked me if I wanted to test Fabula, so, we conducted some tests during a rehearsal open to the audience at the Battersea Arts Centre in London, but none of it was included in the final play. Everything I know about the tool is from sessions with him when we worked on things together.

My observations are these: First, it’s impressive. I appreciate the engineers’ efforts. But the problem is they fed the program books about writing that are not current anymore. Theater needs to reflect the reality here and now. I think this is why they decided not to let the tool be accessible to everybody yet.

Another observation: it’s very strange that you don’t start your writing process from an empty page anymore. The empty page is a pain, but at the same time, it stimulates your creativity. It’s like how for children, being bored is the best way to become creative. You sit in front of the empty page and feel an existential crisis. You need to use all your intuition, and that’s magic.

“It’s very strange that you don’t start your writing process from an empty page anymore. The empty page is a pain, but at the same time, it stimulates your creativity. It’s like how for children, being bored is the best way to become creative.”

Similarly, Lee Sedol said that the Go game is an art form because two players start from an empty board, and everything arises from nothing. It’s the creation of art between two players. In chess, you don’t start with nothing—you start with two armies that control each other. But in programs like Fabula, the empty page is eliminated. The feeling you get is that everything was already written, and you can just make changes. You enter a prompt and get a comprehensive draft of a play with scenes, characters, the answers, and the questions you want to ask the audience. You can change things through the process, but you don’t start from nothing.

Q: Tech startups always look for the pain point. But why is the blank page the pain point? It shouldn’t be the enemy.

Yes, exactly. When I traveled to Seoul, I met with KAIST Professor Chihyung Jeon, who was a witness of the match. His essay “The Alpha Human versus the Korean: Figuring the Human through Technoscientific Networks,” was one of my inspirations. My entire play is told by the AlphaHumans—starting in 2030 and reconstructing the mythological events that started a new religion.

It took Lee Sedol ten years to digest what happened at the Four Seasons. In a recent lecture at Seoul National University, he said that Go used to be a creative act between two players based on intuition. But now all players study AI moves, memorize them, and repeat them on the board.

It’s inspiring and dystopian. It’s like the King Midas story: you touch everything and it changes to gold, but then you touch your food and it changes to gold too, and you touch your daughter and she changes to gold. So you die of hunger, lonely.

“[Lee] said that Go used to be a creative act between two players based on intuition. But now all players study AI moves, memorize them, and repeat them on the board. It’s inspiring and dystopian.”

Who sees whom

Q: Tell me about the structure of your piece. You also play with how the action is shown to the audience.

In my play, the audience is divided into a VIP and a regular audience. Only VIPs can see the game close-up, and the main audience can only see through screens.

The VIP audience represents those who were in the game room at the Four Seasons—big tech chiefs and their families. The main audience represents those in the ballrooms, where sportscasters gave commentary to swarms of journalists—English-speaking and Korean-speaking, and the 200 million watching on screens. That’s the structure of power: who sees whom, who controls whom.

Redefining evil

Q: What does this match tell us about the future of humanity?

The reconstruction of the match wasn’t merely about the game of Go, but about everything. AI experts estimate a 30% risk of human extinction caused by AI. It’s like they’re entering your home, putting a gun to your child’s head, and playing Russian roulette.

I had an amazing two-hour chat with the chief of the Chess Forum in New York City after entering thinking to buy a Go game for myself. He told me that to this day, on Wall Street, they test if someone has the potential to become a big manager by playing games with them. In American companies, they play chess; in Japanese ones, they play Go. In his opinion, the AlphaGo match was testing tools for the real world.

My play starts with the match in Seoul and ends with a scene where a character inspired by Peter Thiel is interrogated by a journalist, and we realize this is all about testing tools to sell them for real war. The truth is they use the same system of algorithms to create autonomous weapons already used in Gaza.

At the end of the play, the journalist watches AI’s victory on the screen at the airport, with big tech companies celebrating. We can read her thoughts as she waits for her flight, trying to put this intense, emotional, exhausting experience together into a new idea of evil.

Q: And you worked on that moment with Google Gemini?

Yes, that’s the main example of how I’ve used AI as a creative tool for writing.

I described the scene: the journalist, a modern version of Hannah Arendt, coming back from the match and looking for a new definition of evil. Hannah Arendt created the idea of “banality of evil” by observing the Eichmann trial in Jerusalem. I started feeding Gemini different inspirations: the legend of the Grand Inquisitor from the Brothers Karamazov, The Society of the Spectacle by Debord, Discipline and Punish by Foucault.

I got some material, worked on it, gave it back, and went back and forth like that. I loved it. The system suggested the idea of “efficiency” as the new definition of evil in the digital age. I love the perversion of working with AI to create a new definition of evil; we need to change our definitions given these tools.

But to do this, you need to create the character based on Hannah Arendt and know her books. You need to know all the other books I mentioned—classic books that are critiques of power structures—and guide the AI precisely to get what you want.

“The system suggested the idea of ‘efficiency’ as the new definition of evil in the digital age. I love the perversion of working with AI to create a new definition of evil.”

And I didn’t copy and paste what I got—I wrote it. Gemini, in this context, was like a perfect digestion tool. It read a lot of stuff and concepts and digested it, which sped things up.

But it was so inspiring. I remember very well the moment I was considering whether to take on AI as the topic of my play. I had this feeling of exhaustion: “Oh my god, you middle-aged woman, you need to learn all these new tools. Why?” But I went through the Driving Innovation with Generative AI course at MIT, all these books, travels, entering DeepMind, testing tools, Seoul…everything. At the end, I had this moment of awe. For me, the final monologue is precisely that.

Q: Do you really feel that the ideas you got from working with Gemini are really new? Do you think it pushed you?

Yes, absolutely. To understand AI and our new epoch, we need new definitions of basic philosophical questions. One of the most basic is the definition of evil. Should we keep the old definition, or should we redefine it so we can better understand what’s happening and where the dangers are?

“To understand AI and our new epoch, we need new definitions of basic philosophical questions. One of the most basic is the definition of evil. Should we keep the old definition, or should we redefine it so we can better understand what’s happening and where the dangers are?”

Q: Do you think you’ll use AI in the future? You had this experience with Gemini where you had a specific goal—redefining evil while working on a play about AI, so the tool fit perfectly. Would you try to recreate this process?

It’s very hard to answer because it’s all very fresh, and I need to digest the experience properly. I had a lot of doubt when I started using it, but I’m very happy that I did. I treat theater and playwriting as a space to play with tools that are dangerous in reality, but when you put them on stage, you can disarm them.

Want to deepen your study? Here is a compilation of some of the resources that informed Natalia’s work:

📚 Books: Supremacy by Parmy Olson | Novacene: The Coming Age of Hyperintelligence by James Lovelock | The Society of the Spectacle by Guy Debord | Discipline and Punish by Michel Foucault | The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky (specifically the “Grand Inquisitor” chapter) | Brave New World by Aldous Huxley | Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil by Hannah Arendt

✍️ Essay: “The Alpha Human versus the Korean: Figuring the Human through Technoscientific Networks” by Professor Chihyung Jeon (KAIST)

📖 Course: Driving Innovation with Generative AI (MIT)

Thank you for reading! If you were forwarded this email, join us below: